tl;dr: Some insightful notes from the moonmath book. Introdcue definitions of formal language, R1CS and quadratic arithmetic program in zero-knowledge proof systems.

$$ \def\Adv{\mathcal{A}} \def\Badv{\mathcal{B}} \def\vect#1{\mathbf{#1}} $$

Notes on chapter 6 of moon-math book. This blog focuses on the formal language and its representation in modern zero-knowledge proofs.

Formal Language and Proof

Before diving into zero-knowledge proofs, it is essential to formally deconstruct the core meaning of the term “proof.” In traditional mathematical proofs, the process involves starting from a set of axioms and applying rigorous logical deductions to reach the desired conclusion. However, the setting of zero-knowledge proofs in cryptography differs from the proof of mathematical theorems, which typically involves statements such as “claim A is true” or the knowledge of a secret string that belongs to a formal language.

Formal Language

Roughly speaking, a formal language (or just language for short) is a set of words. Words, in turn, are strings of letters taken from some alphabet, and formed according to some defining rules of the language.

Definition.(Formal Languages). Let \(\sum\) be any set and \(\sum^*\) the set of all strings of finite length \(\lbrace x_1, \ldots,x_n \rbrace\) with \(x_j \in \sum\) including the empty string \(\lbrace\rbrace \in \sum^*\).

- Language: A language \(\mathcal{L}\), in its most general definition, is a subset of the set of all finite strings \(\sum^*\).

- Alphabet: The set \(\sum\) is called the alphabet of the language \(\mathcal{L}\).

- Letter: \(x \in \sum\) is called a letter.

- Word: \(x \in \mathcal{L}\) is called a letter.

- Grammar: If there are rules that specify which strings from \(\sum^*\) belong to the language and which don’t, those rules are called the grammar of the language.

- Equivalent Language: \(\mathcal{L}_1 \iff \mathcal{L_2}\) means they have the same alphabet and words.

Decision Function

The definition of formal languages is very general, and does not cover many subclasses of languages known in the literature. However, in the context of SNARK development, languages are commonly defined as decision problems where a so-called deciding relation \(R \subset \Sigma^*\) decides whether a given string \(x \in \Sigma^*\) is a word in the language or not. If \(x \in R\) then \(x\) is a word in the associated language \(L_R\), and if \(x \notin R\) then it is not. The relation \(R\) therefore summarizes the grammar of language \(L_R\).

Unfortunately, in some literature on proof systems, \(x \in R\) is often written as \(R(x)\), which is misleading since, in general, \(R\) is not a function, but a relation in \(\Sigma^*\). For the sake of clarity, we therefore adopt a different point of view and work with what we might call a decision function instead:

\[R: \Sigma^* \rightarrow\{\text { true }, \text { false }\}\]Decision functions decide if a string \(x \in \Sigma^*\) is an element of a language or not. In case a decision function is given, the associated language itself can be written as the set of all strings that are decided by \(R\):

\[L_R:=\left\{x \in \Sigma^* \mid R(x)=\text { true }\right\}\]In the context of formal languages and decision problems, a statement \(S\) is the claim that language \(L\) contains a word \(x\), that is, a statement claims that there exists some \(x \in L\). A constructive proof for statement \(S\) is given by some string \(P \in \Sigma^*\) and such a proof is verified by checking if \(R(P)=\) true. In this case, \(P\) is called an instance of the statement \(S\).

Example (Alternating Binary strings). To consider a very basic formal language with a decision function, define language \(L_{a l t}\) as the set of all finite binary strings where a 1 must follow a 0 and vice versa. Attempting to write the grammar of this language in a more formal way, we can define the following decision function:

\[R:\{0,1\}^* \rightarrow\{\text { true }, \text { false }\} ;<x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_n>\mapsto \begin{cases}\text { true } & x_{j-1} \neq x_j \text { for all } 1 \leq j \leq n \\ \text { false } & \text { else }\end{cases}\]Instance and Witness

As we have seen in the previous paragraph, statements provide membership claims in formal languages, and instances serve as constructive proofs for those claims. However, in the context of zero-knowledge proof systems, our notion of constructive proofs is refined in such a way that it is possible to hide parts of the proof instance and still be able to prove the statement. In this context, it is therefore necessary to split a proof into an unhidden, public part called the instance and a hidden, private part called a witness. While statements in the sense of the previous section can be seen as membership claims, statements in the refined definition can be seen as knowledge-claims, where a prover claims knowledge of a witness for a given instance.

To account for this separation of a proof instance into an instance and a witness part, our previous definition of formal languages needs a refinement. Instead of a single alphabet, the refined definition considers two alphabets \(\Sigma_I\) and \(\Sigma_W\), and a decision function defined as follows:

\[R: \Sigma_I^* \times \Sigma_W^* \rightarrow\{\text { true, false }\} ;(i ; w) \mapsto R(i ; w)\]Words are therefore strings \((i ; w) \in \Sigma_I^* \times \Sigma_W^*\) with \(R(i ; w)=\) true. The refined definition differentiates between inputs \(i \in \Sigma_I\) and inputs \(w \in \Sigma_W\). The input \(i\) is called an instance and the input \(w\) is called a witness of \(R\).

If a decision function is given, the associated language is defined as the set of all strings from the underlying alphabets that are verified by the decision function:

\[L_R:=\left\{(i ; w) \in \Sigma_I^* \times \Sigma_W^* \mid R(i ; w)=\text { true }\right\}\]In this refined context, a statement \(S\) is a claim that, given an instance \(i \in \Sigma_I^*\), there is a witness \(w \in \Sigma_W^*\) such that language \(L\) contains a word \((i ; w)\). A constructive proof for statement \(S\) is given by some string \(P=(i ; w) \in \Sigma_I^* \times \Sigma_W^*\), and a proof is verified by \(R(P)=\) true. Given some instance, there are proof systems able to prove the statement (at least with high probability) without revealing anything about the witness. In this sense, the witness is often called the private input, and the instance is called the public input.

Example.(Knowledge of SHA256 Preimage)

An appropriate alphabet \(\Sigma_I\) for the set of all instances, and an appropriate alphabet \(\Sigma_W\) for the set of all witnesses is therefore given by the set \(\{0,1\}\). A proper decision function is given as follows:

\[R_{S H A 256}:\{0,1\}^* \times\{0,1\}^* \rightarrow\{\text { true }, \text { false }\} \\ (i ; w) \mapsto \begin{cases}\text { true } & |i|=256, i=\operatorname{SHA} 256(w) \\ \text { false } & \text { else }\end{cases}\]We write \(L_{S H A 256}\) for the associated language, and note that it consists of words that are strings \((i ; w)\) such that the instance \(i\) is the SHA256 image of the witness \(w\). Given some instance \(i \in\{0,1\}^{256}\), a statement in \(L_{S H A 256}\) is the claim “Given digest \(i\), there is a preimage \(w\) such that \(S H A 256(w)=i^{\prime \prime}\), which is exactly what the knowledge-of-preimage problem is about. A constructive proof for this statement is therefore given by a preimage \(w\) to the digest \(i\) and proof verification is achieved by verifying that \(S H A 256(w)=i\).

Modularity

In order to synthesize statements, developers then combine predefined gadgets into complex logic. We call the ability to combine statements into more complex statements modularity. To understand the concept of modularity on the level of formal languages defined by decision functions, we need to look at the intersection of two languages, which exists whenever both languages are defined over the same alphabet. In this case, the intersection is a language that consists of strings which are words in both languages.

To be more precise, let $L_1$ and $L_2$ be two languages defined over the same instance and witness alphabets $\Sigma_I$ and $\Sigma_W$. The intersection $L_1 \cap L_2$ of $L_1$ and $L_2$ is defined as follows:

\[L_1 \cap L_2:=\left\{x \mid x \in L_1 \text { and } x \in L_2\right\}\]If both languages are defined by decision functions $R_1$ and $R_2$, the following function is a decision function for the intersection language $L_1 \cap L_2$ :

\[R_{L_1 \cap L_2}: \Sigma_I^* \times \Sigma_W^* \rightarrow\{\text { true }, \text { false }\} ;(i, w) \mapsto R_1(i, w) \text { and } R_2(i, w)\]Thus, the intersection of two decision-function-based languages is also decision-function-based language. This is important from an implementation point of view: it allows us to construct complex decision functions, their languages and associated statements from simple building blocks. Given a publicly known instance $I \in \Sigma_I^*$, a statement in an intersection language claims knowledge of a witness that satisfies all relations simultaneously.

Rank-1 Constraint Systems

Rank-1 (Quadratic) Constraint Systems abbr. R1CS are a class of languages that are particularly useful in the context of zero-knowledge proofs. They are defined over finite fields and consist of a set of quadratic equations that must be satisfied by a pair of strings, one representing the public instance and the other representing the private witness.

R1CS Satisfiability Language

The core idea is to express the decision function in terms of a system of quadratic equations over a finite field. This is particular useful for pairing-based proving systems. See SNARKs for C: Verifying Program Executions Succinctly and in Zero Knowledge for formal definition/proofs of R1CS.

Definition (R1CS): Let $\mathbb{F}$ be a finite field, $n$ the dimension of Instance (number of public inputs), $m$ the dimension of Witness (number of private inputs), $k$ the number of constraints. Let $x=(1, I, W) \in \mathbb{F}^{1+n+m}$ is a $(n+m+1)$-dimensional vector, $A, B, C$ are $(n+m+1) \times k$-dimensional matrices and $\odot$ is the Schur/Hadamard product, then a R1CS can be written as follows:

\[A x \odot B x=C x\]To be more specific, the $k$ constraints are given as follows:

\[\begin{gathered} \left(a_0^1+\sum_{j=1}^n a_j^1 \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m a_{n+j}^1 \cdot W_j\right) \cdot\left(b_0^1+\sum_{j=1}^n b_j^1 \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m b_{n+j}^1 \cdot W_j\right)=c_0^1+\sum_{j=1}^n c_j^1 \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m c_{n+j}^1 \cdot W_j \\ \vdots \\ \left(a_0^k+\sum_{j=1}^n a_j^k \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m a_{n+j}^k \cdot W_j\right) \cdot\left(b_0^k+\sum_{j=1}^n b_j^k \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m b_{n+j}^k \cdot W_j\right)=c_0^k+\sum_{j=1}^n c_j^k \cdot I_j+\sum_{j=1}^m c_{n+j}^k \cdot W_j \end{gathered}\]If a pair of strings of field elements $\left(<I_1, \ldots, I_n>\right.$; $<$ $W_1, \ldots, W_m>$ ) satisfies theses equations, $<I_1, \ldots, I_n>$ is called an instance and $<W_1, \ldots, W_m>$ is called a witness of the system.

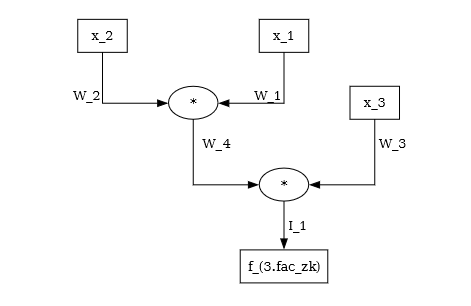

Example(Proof of 3-Factorization). Let $L_{3.fac}$ be the 3-factorization language. $L_{3.fac}$ consists of words $I_1, W_1, W_2, W_3$ over the alphabet $\mathbb{Z}^{+}$ (or finite field $\mathbb{F}_q$) such that $I_1 = W_1 \cdot W_2 \cdot W_3$. We can flatten the cubic constraint to quadratic equation system by introducing extra temporary variables. The following is one of the R1CS expressions:

\[\begin{cases} W_1 \cdot W_2 = W_4 \\ W_4 \cdot W_3 = I_1 \end{cases}\]with $n = 1, m = 4, k = 2$ and $A,B,C$ matrix (omitted here).

Generally speaking, the idea of a Rank-1 Constraint System is to keep track of all the values that any variable can hold during a computation, and to bind the relationships among all those variables that are implied by the computation itself. Once relations between all steps of a computer program are constrained, program execution is then enforced to be computed in exactly in the expected way without any opportunity for deviations. In this sense, solutions to Rank-1 Constraint Systems are proofs of proper program execution.

The R1CS satisfiability language is obtained by the union of all R1CS languages. To be more precise, let the alphabet $\sum = \mathbb{F}$ be a field. Then the language $L_{R1CS_SAT(\mathbb{F})}$ is defined as follows:

\[L_{R 1 C S \_S A T(\mathbb{F})}=\left\{(i ; w) \in \Sigma^* \times \Sigma^* \mid \text { there is a R1CS } R \text { such that } R(i ; w)=t r u e\right\}\]R1CS Modularity. Let $S_1$ and $S_2$ be two R1CS over $\mathbb{F}$. A new R1CS $S_3$ is obtained by the intersection of $S_1$ and $S_2$, that is, $S_3=S_1 \cap S_2$. In this context, intersection means that both the equations of $S_1$ and the equations of $S_2$ have to be satisfied in order to provide a solution for the system $S_3$. As a consequence, developers are able to construct complex R1CS from simple ones.

Algebraic Circuits

Solving the systems of quadratic equations is generally NP-hard. Given an instance $I$, finding the witness $W$ such that $R(I ; W)=$ true is a hard problem and thus may makes it secure against malicious attacks. However, for some proving systems (e.g., hashing preimage proof), it’s expected that given a witness $W$ (e.g., the preimage), finding the public instance $I$ (e.g. hashing value) such that $R(I ; W)=$ true is easy (in polynomial time). Rank-1 Constraint Systems are therefore impractical from a provers perspective and auxiliary information is needed that helps to compute solutions $I$ efficiently. This witness/instance generation can be usually performed as a progarm, or more generally, as a circuit. Algebraic Circuits are a class of circuits involving only addition and multiplication operations that are particularly useful in the context of zero-knowledge proofs.

- Every algebraic circuit defines an associated R1CS and (may) also provides an efficient way to compute solutions $I$ with a given witness $W$ for that R1CS.

- Every R1CS can be expressed as an algebraic circuit. This can be achieved by defining temporary variables for every multiplication/addiction operation in the R1CS.

For more details about algebraic circuits and their relation to R1CS, one can refer to Ben-Sasson et al. 2013 and chapters 6,7 of moon-math book. A formal definition of algebraic circuits taken from the moon-math book is given below:

Definition (Algebraic Circuits). Let $\mathbb{F}$ be a field. An algebraic circuit is a directed acyclic (multi-)graph that computes a polynomial function over $\mathbb{F}$. Nodes with only outgoing edges (source nodes) represent the variables and constants of the function and nodes with only incoming edges (sink nodes) represent the outcome of the function. All other nodes have exactly two incoming edges and represent the field operations addition as well as multiplication. Graph edges are directed and represent the flow of the computation along the nodes.

To be more precise, a directed acyclic multi-graph $C(\mathbb{F})$ is called an algebraic circuit over $\mathbb{F}$ if the following conditions hold:

- The set of edges has a total order.

- Every source node has a label that represents either a variable or a constant from the field $\mathbb{F}$.

- Every sink node has exactly one incoming edge and a label that represents either a variable or a constant from the field $\mathbb{F}$.

- Every node that is neither a source nor a sink has exactly two incoming edges and a label from the set ${+, *}$ that represents either addition or multiplication in $\mathbb{F}$.

- All outgoing edges from a node have the same label.

- Outgoing edges from a node with a label that represents a variable have a label.

- Outgoing edges from a node with a label that represents multiplication have a label, if there is at least one labeled edge in both input path.

- All incoming edges to sink nodes have a label.

- If an edge has two labels $S_i$ and $S_j$ it gets a new label $S_i=S_j$.

- No other edge has a label.

- Incoming edges to labeled sink nodes, where the label is a constant $c \in \mathbb{F}$ are labeled with the same constant. Every other edge label is taken from the set ${W, I}$ and indexed compatible with the order of the edge set.

To get a better intuition of above definition, let $C(\mathbb{F})$ be an algebraic circuit. Source nodes are the inputs to the circuit and either represent variables or constants. In a similar way, sink nodes represent termination points of the circuit and are either output variables or constants. Constant sink nodes enforce computational outputs to take on certain values. Nodes that are neither source nodes nor sink nodes are called arithmetic gates (multiplication/addition gates). An example of the 3-factorization circuit is given below:

Quadratic Arithmetic Programs

One reason why those systems are useful in the context of succinct zero-knowledge proof systems is because any R1CS can be transformed into another computational model called a Quadratic Arithmetic Program abbr. QAP, which serves as the basis for some of the most efficient succinct non-interactive zero-knowledge proof generators that currently exist. As we will see, proving statements for languages that have decision functions defined by Quadratic Arithmetic Programs can be achieved by providing certain polynomials, and those proofs can be verified by checking a particular divisibility property of those polynomials.

Definition(Quadratic Arithmetic Programs). Let $\mathbb{F}$ be a field and $R$ a Rank-1 Constraint System over $\mathbb{F}$ such that the number of non-zero elements in $\mathbb{F}$ is strictly larger than the number $k$ of constraints in $R$. Moreover, let $a_j^i, b_j^i$ and $c_j^i \in \mathbb{F}$ for every index $0 \leq j \leq n+m$ and $1 \leq i \leq k$, be the defining constants of the R1CS and $m_1, \ldots, m_k$ be arbitrary, invertible and distinct elements from $\mathbb{F}$.

Then a Quadratic Arithmetic Program associated to the R1CS $R$ is the following set of polynomials over $\mathbb{F}$:

\[Q A P(R)=\left\{T \in \mathbb{F}[x],\left\{A_j, B_j, C_j \in \mathbb{F}[x]\right\}_{j=0}^{n+m}\right\}\]Here $T(x):=\Pi_{l=1}^k\left(x-m_l\right)$ is a polynomial of degree $k$, called the target polynomial of the QAP and $A_j, B_j$ as well as $C_j$ are the unique degree $k-1$ polynomials defined by the following equation:

\[A_j\left(m_i\right)=a_j^i, \quad B_j\left(m_i\right)=b_j^i, \quad C_j\left(m_i\right)=c_j^i \quad \text { for all } j=1, \ldots, n+m+1, i=1, \ldots, k\]Given some Rank-1 Constraint System, an associated Quadratic Arithmetic Program is therefore a set of polynomials, computed from the constants in the R1CS. To see that the polynomials $A_j, B_j$ and $C_j$ are uniquely defined by the equations, recall that a polynomial of degree $k-1$ is completely determined by $k$ evaluation points and it can be computed for example by Lagrange interpolation. Computing a QAP from any given R1CS can be achieved in the following three steps.

- If the R1CS consists of $k$ constraints, first choose $k$ different, invertible element from the field $\mathbb{F}$. Every choice defines a different QAP for the same R1CS.

- Compute the target polynomial $T$ according to its definition.

- Use Lagrange’s method to compute the polynomials $A_j, B_j, C_j$ for every $1 \leq j \leq k$.

One of the major points of Quadratic Arithmetic Programs in proving systems is that solutions of their associated Rank-1 Constraint Systems are in 1:1 correspondence with certain polynomials $P$ divisible by the target polynomial $T$ of the QAP. Verifying solutions to the R1CS and hence, checking proper circuit execution is then achievable by polynomial division of $P$ by $T$.

QAP Satisfiability

Let $R$ be some Rank-1 Constraint System with associated variables $\left(<I_1, \ldots, I_n>;<W_1, \ldots, W_m>\right)$ and let $Q A P(R)$ be a Quadratic Arithmetic Program of $R$. Then the string $\left.\left(<I_1, \ldots, I_n\right\rangle ;<W_1, \ldots, W_m>\right)$ is a solution to the R1CS if and only if the following polynomial is divisible by the target polynomial $T$ :

\[\begin{aligned} P_{(I ; W)} = &\left(A_0+\sum_j^n I_j \cdot A_j+\sum_j^m W_j \cdot A_{n+j}\right) \cdot\left(B_0+\sum_j^n I_j \cdot B_j+\sum_j^m W_j \cdot B_{n+j}\right) \\ &-\left(C_0+\sum_j^n I_j \cdot C_j+\sum_j^m W_j \cdot C_{n+j}\right) \end{aligned}\]since $P(x)$ has roots in $(m_1, \cdots, m_{k})$. To understand how Quadratic Arithmetic Programs define formal languages, observe that every QAP over a field $\mathbb{F}$ defines a decision function over the alphabet $\Sigma_I \times \Sigma_W=\mathbb{F} \times \mathbb{F}$ in the following way:

\[R_{Q A P}:(\mathbb{F})^* \times(\mathbb{F})^* \rightarrow\{\text { true }, \text { false }\} ;(I ; W) \mapsto \begin{cases}\text { true } & P_{(I ; W)} \text { is divisible by } T \\ \text { false } & \text { else }\end{cases}\]

Circuits, R1CS and QAP.

A generic proof system can be constructed from a circuit, then to R1CS and finally to QAP. Verifying a proof in the three representations is different:

- Verifying a constructive proof in the case of a circuit is achieved by executing the circuit and then by comparing the result against the given proof.

- Verifying the proof in the R1CS means checking if the elements (witness) of the proof satisfy the R1CS equations.

- Verifying a proof in the QAP is done by polynomial division of the proof polynomial $P$ by the target polynomial $T$. The proof is verified if and only if $P$ is divisible by $T$.

In this sense, the QAP representation is a more abstract (also more convenient) representation of proof system and requires verification of a polynomial divisibility property. This mathematical property is much easier to check in zero-knowledge than the others. The Groth16 proving system is the first efficient and practical proof system that follows the transformation from circuit to R1CS and then to QAP. The R1CS and circuit representations are typically used as intermediate representations in the proof generation process. As the lowest level representation of the proof system, the algeraic circuit can be efficiently generated by high-level programming languages (e.g., circom, rust, etc.). In circom, we only need to define the circuit and the compiler will automatically generate the final proof system (circuit -> R1CS -> QAP) based on our chosen backend protocol (e.g., Groth16, Plonk, etc.).